Paul Heyman: Theater of the Margins

/Every art form, when it endures, develops not only technique but ritual. Rules harden, boundaries are set, and the audience learns to expect structure as much as surprise. But eventually, the form forgets why it began. The gestures remain, but the spirit dulls. The cathedral still stands—but no one hears the choir. When this happens, revitalization does not come from renovation within. It comes from the fringe, from the fool, the outlaw, or the heretic who refuses to play by the accepted rules.

In professional wrestling—a form long misunderstood, long dismissed—this moment of rupture came through a wiry, hyper-verbal New Yorker named Paul Heyman, whose small promotion, Extreme Championship Wrestling, became a revival tent of unholy liturgy in the mid-1990s.

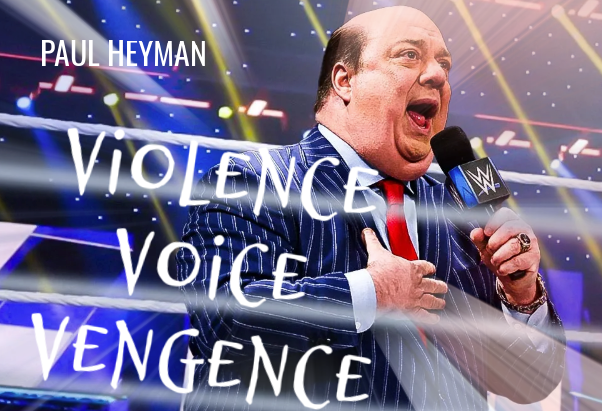

Heyman did not invent wrestling, any more than the Ramones invented music. What he did was purify it. He stripped it down to violence, voice, and vengeance. He removed the pretense of legitimacy but left in the raw emotion. He let the audience see the strings—and then used the strings to strangle the illusion. In doing so, he invited the fans to believe again, not in kayfabe, but in wrestling as drama, rebellion, and renewal.

The Old World Order

For most of the 20th century, wrestling operated as a closed system, governed by kayfabe and cartel. The National Wrestling Alliance divided the country into territories, each with its own regional stars, promoters, and loyalties. Champions were chosen not merely for athleticism or charisma but for their ability to “carry the belt” in real life—to protect the illusion, travel constantly, and negotiate backstage politics with care.

The fans were participants in a shared fiction. They knew, perhaps vaguely, that the matches were predetermined, but they accepted the performance as meaningful. Betrayals hurt. Victories mattered. The blood, though often theatrical, felt real. Wrestling was less a sport than a ritualized morality play, with good and evil fighting in tights and boots instead of robes and incense.

But by the mid-1990s, that world had crumbled. National television deals, the decline of the territory system, and the rise of Vince McMahon and corporate wrestling turned once-regional art into overproduced spectacle. The matches became formulaic. The danger evaporated. The audience became restless.

Then came Heyman.

Heyman's Rebellion

Heyman’s genius was not just in what he booked, but who and how. He didn’t seek the chiseled stars and comic book heroes of WWF or the aging icons of WCW. He collected misfits, has-beens, wild men, and cult heroes: men with scars, with records, with chips on their shoulders and something to prove. In ECW, broken men were not rehabilitated—they were unleashed.

He shot promos in locker rooms, alleys, and parking lots. He encouraged profanity, blood, and real-life grudges. He handed out microphones like weapons and told his wrestlers to speak their truth, whether it fit the storyline or not.

And most importantly—he turned the audience into co-conspirators. This was the heart and soul of his revolution.

ECW fans were not passive. They were initiates. They chanted, cursed, threw chairs, and cheered things that other wrestling audiences weren’t even allowed to see. They knew the business, knew the dirt sheets, knew what was a shoot and what was a work—and Heyman rewarded them by turning that knowledge into the show itself.

It was not polished. It was feral theater. But it was alive.

The Business as the Story

In the closed-world kayfabe era, the business of wrestling—the contracts, the booking, the politics—was never part of the narrative. But in ECW, and later in the broader revolution it helped spark, the business itself became the story.

A wrestler didn’t just turn heel—he walked out on a handshake deal. A title wasn’t just won or lost—it was dropped because someone no-showed, or got fired, or was leaving for a better offer. When Shane Douglas threw down the NWA World Title (literally trashing the famous “ten pounds of gold” belt!) and declared ECW independent, it was not merely a plot point. It was a declaration of rebellion, staged as a moment of theater, but vibrating with real-world consequence.

Fact and fiction were now intermingled in a way never before in the history of the dramatic arts.

And this meta-awareness spread. Scott Hall’s 1996 Nitro debut, the rise of the nWo, the Mr. McMahon character, the Montreal Screwjob, the entire Attitude Era—all of it grows out of the seed Heyman planted: that the audience can be trusted with reality, so long as reality is made mythic.

Heyman showed that the greatest heat didn’t come from fantasy—it came from truth, weaponized.

A Sacred Spectacle

Violence in ECW was not a gimmick. It was a form of confession. Tables, barbed wire, fire—these weren’t just props; they were sacraments. The violence wasn’t staged for shock value alone, but for authenticity. Wrestlers bled because life was hard, because they had nothing else to offer, because the audience deserved it.

This was not the wrestling of Madison Square Garden. This was the bingo hall gospel: loud, ugly, participatory, and raw. There was no illusion of safety, and therefore no barrier to belief. ECW wasn’t fake. It was true.

Heyman, like any good showman-priest, knew how to manage chaos without appearing to. He let the crowd feel like it was running the show, while quietly shaping every beat. He played to the smart fans, the angry fans, the disillusioned believers who didn’t want kayfabe back, but wanted something to believe in. What he offered them was not certainty—but conviction.

Failure, Again, as Victory

ECW didn’t last. It was too violent, too unstable, too indebted. The company folded in 2001. The wrestlers moved on. WWE bought the library and absorbed it. The brand became a corporate asset within the WWE empire.

But like the Ramones, ECW’s failure was its fulfillment.

Heyman didn’t change wrestling by winning. He changed it by altering the conditions under which victory could be defined. After ECW, the industry could never again pretend the audience didn’t know the game. It could never again hide behind kayfabe alone. Every promotion that came after—whether they copied ECW or tried to erase it—was responding to the new logic Heyman had introduced: that wrestling is not pretending to be real, it is real pretending.

His influence lives in AEW, in the “pipebomb” promo, in every moment where the camera lingers too long on an unscripted reaction, in every storyline that whispers, “What if this one isn’t fake?”

Conclusion: The Heretic and the High Priest

Paul Heyman did not look like a revolutionary. He looked like a manager at a downtown copy shop. But in a strip mall in Philadelphia, he rebuilt wrestling from the floor up, using only noise, belief, and a locker room full of men with nothing to lose.

He did not save the art form by preserving its traditions. He saved it by reminding us what it was for: to let people scream, and bleed, and matter, even if only for ten minutes under the lights.

Barzun teaches us that cultural renewal often begins in places that look like collapse. That the true guardians of civilization are sometimes mistaken for vandals. And that when the stage goes dark, it is the back alley or the bingo hall that lights the next fire.

Heyman lit that fire. And it burned beautifully.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, My Name is Paul Heyman!”

And now, a generation later, he is at the center of the most celebrated storyline in modern wrestling. The wise man. The consigliere. The anchor of The Bloodline saga. What do we make of that?

We accept the irony. We accept that the revolutionary becomes the establishment, that the heretic is invited back into the temple—sometimes even as high priest. The cycle continues. And in this case, we say simply: Congratulations, Wise Man. Well done. You earned it.

And then, we enjoy his performance—because it is, unmistakably, in continuity with what he began long ago in South Philly. Still unpredictable, layered, dangerous, and alive.

The bingo hall never really closed. It just moved to prime time.

(Part 3/4 in this essay series)