The Ramones: Cultural Renewal from the Margins

/In any age, the mainstream is both myth and machinery. It claims to be the destination of talent, the proof of value, the reward of refinement—but it is also a filtering device, designed to admit only what conforms to its aesthetics, marketing logics, and institutional tastes. The machinery includes the labels, the critics, the award shows, the charts. The myth is the illusion that these institutions recognize greatness, rather than merely manage visibility.

By the 1970s, rock music had become particularly vulnerable to this machinery. What had begun in the two decades prior as a kinetic outburst of rhythm and soul had, by mid-decade, ossified into pageantry. Stadium shows required budgets. Songs grew longer, lusher, less urgent. The rock star was no longer a threat to the establishment—he was the establishment.

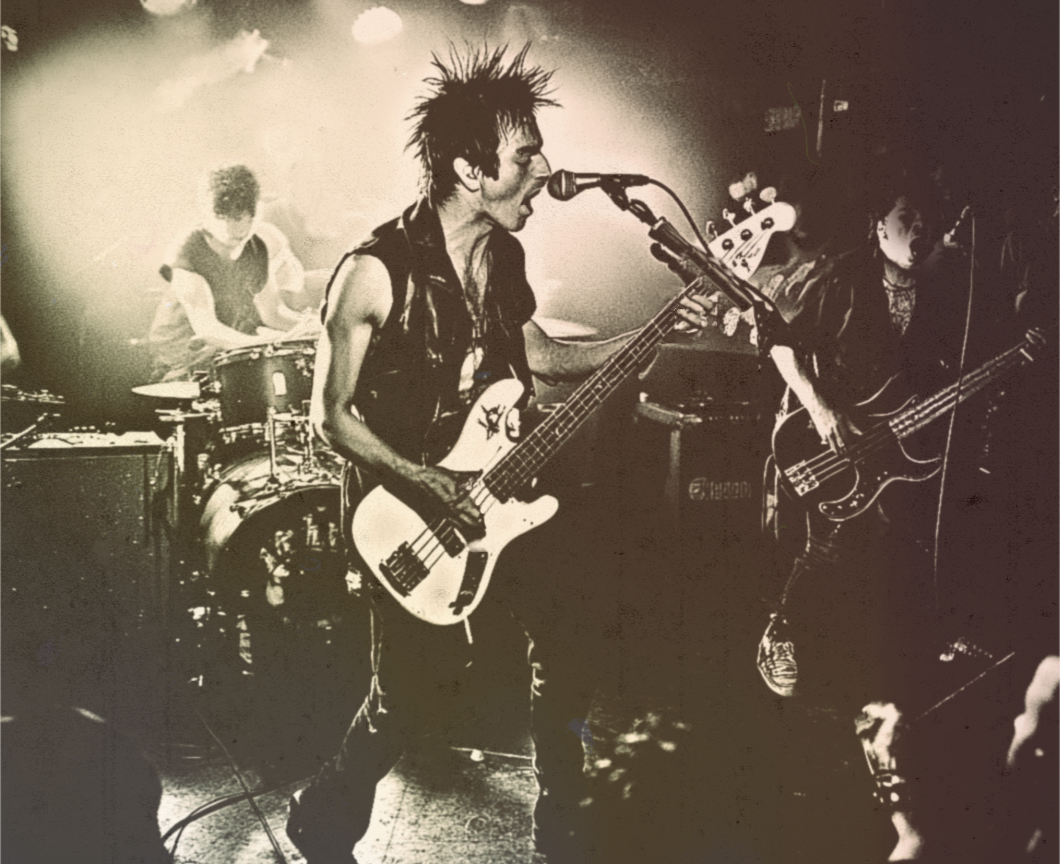

Into this world came The Ramones, four oddballs from Forest Hills who didn’t look like anyone’s idea of a headliner, couldn’t play like the virtuosos on the radio, and had no evident place in the system at all.

And yet—they wanted in. That’s the paradox.

The Ramones didn’t set out to burn down the house. They wanted to play inside it. They loved the girl groups, the British Invasion, and bubblegum pop. They longed to be pop stars, adored by teenagers and welcomed onto American Bandstand. But what emerged from their collaboration was something entirely different: a new ethic of performance, rooted in velocity, minimalism, and refusal. They didn’t become what they dreamed—they became something greater, and ultimately timeless.

Three Chords and the Truth

There was nothing accidental about their sound. It was stripped-down on purpose. A Ramones song did not build or swell—it attacked. The songs were short because they had nothing to prove. No solos. No bridges. Barely any endings. Joey’s vocals were somewhere between a chant and a whine, unpolished and deadpan, yet unmistakably human—a voice that could be mocked but never imitated. (You could say the same of Louis Armstrong, Johnny Cash, or Bob Dylan—voices dismissed by critics, imitated by comics, and yet impossible to replace.)

Everything was deliberate: the matching leather jackets, the blank stares, the economy of motion. Where other bands courted transcendence, the Ramones delivered precision simplicity—which, in their hands, became electrifying. They brought energy without decoration, which is to say: ethics.

You might say they brought:

A New Kind of Virtue

What punk introduced was not merely a sound but a set of moral priorities. It refused excess, performance for its own sake, and virtuosity as a credential. What mattered was sincerity, velocity, and presence. To be in the moment, not to narrate it.

And—to a certain extent—to take the moment with you. Hence the importance of melody in punk. That’s why people still hum “Blitzkrieg Bop” decades later—it wasn’t just energy. It was catchy.

In this way, punk was not the enemy of artistry—it was its conscience. And the Ramones were not lazy musicians. They rehearsed relentlessly, tracked obsessively, and held themselves to standards no critic could see. They may not have looked like professionals, but they were never casual. They simply redefined what professional meant.

This, too, is part of the larger pattern Barzun names: when an art form becomes over-theorized, exhausted by its own vocabulary, a new one appears—not just to vandalize, but to purify.

Failure as Fulfillment — The Paradox

Of course, they did not succeed on their own terms. The Ramones never had a number-one hit. They were never the pop stars they aspired to be. They did not break into the machinery of the mainstream—except as a curiosity, a warning, or later, a mascot. But in failing to become popular, they became permanent.

What the Ramones did was harder than sell records. They retooled the culture’s ear. They created a vocabulary that more marketable bands would later adopt. Without the Ramones, there is no Nirvana, no Green Day, no American Idiot on Broadway. Even U2, with their stadium reverence and moral uplift, owes a direct debt. Bono has said the Ramones taught him to believe in raw expression—and that Joey Ramone's voice never left his head. The first track on Songs of Innocence is appropriately The Miracle (Of Joey Ramone).

They may have been too strange, too fast, too unpolished to win the favor of their time—but they became the measure of what would last beyond it.

A Canon of the Margins

Today, the Ramones are canonical. Their logo is worn by people who’ve never heard “Beat on the Brat.” They are rightly taught in courses, lionized in documentaries, referenced in museum exhibits. But this canonization risks obscuring the depth of their gift. They were not merely “early” or “raw.” They were correct. Their instincts were not precursors—they were judgments. They heard what was false in the age, and they answered it not with theory, but with rhythm, noise, and uniform haircuts. What they proved—like jazz before them, like the mystery plays, like the founders of empires—is that refinement is not always evolution, and technical mastery is not the same as artistic power.

The Ramones wanted what the mainstream could not give them—and what it didn’t understand they were giving in return. They didn’t make it inside the machine, but they changed what the machine would later run on. And in doing so, they revealed the deeper pattern: that cultural renewal comes not from the center of power, but from the margins of refusal.

In their three-chord thunder, they taught us something Barzun himself might have recognized: that when forms grow hollow and belief dries up, truth returns in strange garments.

And sometimes, it wears a leather jacket and counts off:

“1-2-3-4!”

(Part 2/4 in this essay series)