Before the Deluge: The Early Beatles and the Art of the Possible

/There is a curious blindness that often afflicts hindsight, a flattening of the past beneath the weight of what followed. We look back through the smoke of revolutions, and what was once incendiary appears quaint, even cute. So it is with the early Beatles.

“Please Please Me,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand” — these are songs that the modern ear, dulled by decades of sonic experimentation, is tempted to dismiss as merely cheerful, merely pop. That is the verdict of the latecomer. This was my public verdict when I first heard the Beatles in junior high — but in private, I kept the guilty pleasure of loving those songs all the same. Perhaps more.

But to hear these songs rightly, one must return not to the fullness of the Beatles' later years, but to the emptiness they filled:

In 1962, the great fire of 1956 still glowed faintly in memory. That earlier year had unleashed a torrent of American vitality: Elvis Presley snarled and shimmied his way into history, Chuck Berry wrote the teenaged myth in three chords, Little Richard screamed theology into dance halls, and Jerry Lee Lewis pounded the piano like it was a rival lover. It was a year of glorious rupture — where the raw, rhythmic, racial undercurrents of American music surged into the mainstream. Rock and roll was not merely entertainment then; it was insurgency.

But revolutions age quickly in commercial cultures. By 1962, the aftershocks of that eruption had begun to fade. Elvis had entered the army, been softened by Hollywood, and emerged safer. Chuck Berry was mired in legal trouble. Little Richard had briefly retreated into the pulpit. And Jerry Lee Lewis — yes, by then — had largely imploded under the weight of scandal and exile, his career derailed after marrying his 13-year-old cousin in 1958. The dangerous edge of rock and roll had not disappeared, but it had been sequestered, gentrified by teen idols and diluted into safer forms.

What remained on the radio was a fraying patchwork: Tin Pan Alley sentimentalism, doo-wop forms nearing exhaustion, and a parade of polite white crooners murmuring borrowed soul through lacquered smiles. The production was smooth. The voices were clean. The dial was safe.

In this context, the Beatles did not enter as heirs to a stable tradition. They arrived as a shock of coherence — a self-contained unit that played, wrote, and harmonized with energy that felt at once old and utterly new. They were not revivalists of 1956; they were revolutionaries of 1963, resynthesizing the fragments of American invention into a form that Britain, and then the world, could claim as its own.

These fragments I have shored against my ruin.

— T.S. Eliot, “The Waste Land”

The early Beatles songs, far from being naive juvenilia, were compact detonations of musical intelligence. Consider “She Loves You.” It begins, outrageously and explosively, with the chorus — a move still rare in songwriting. It shifts perspective into the third person, breaking the solipsism of teenage love songs. And it ends not with resolution but with reflection: “With a love like that, you know you should be glad.” Even the final chord — a jangling major sixth, as my musical friends have informed me — felt like a door flung open. And indeed it was. The world had changed.

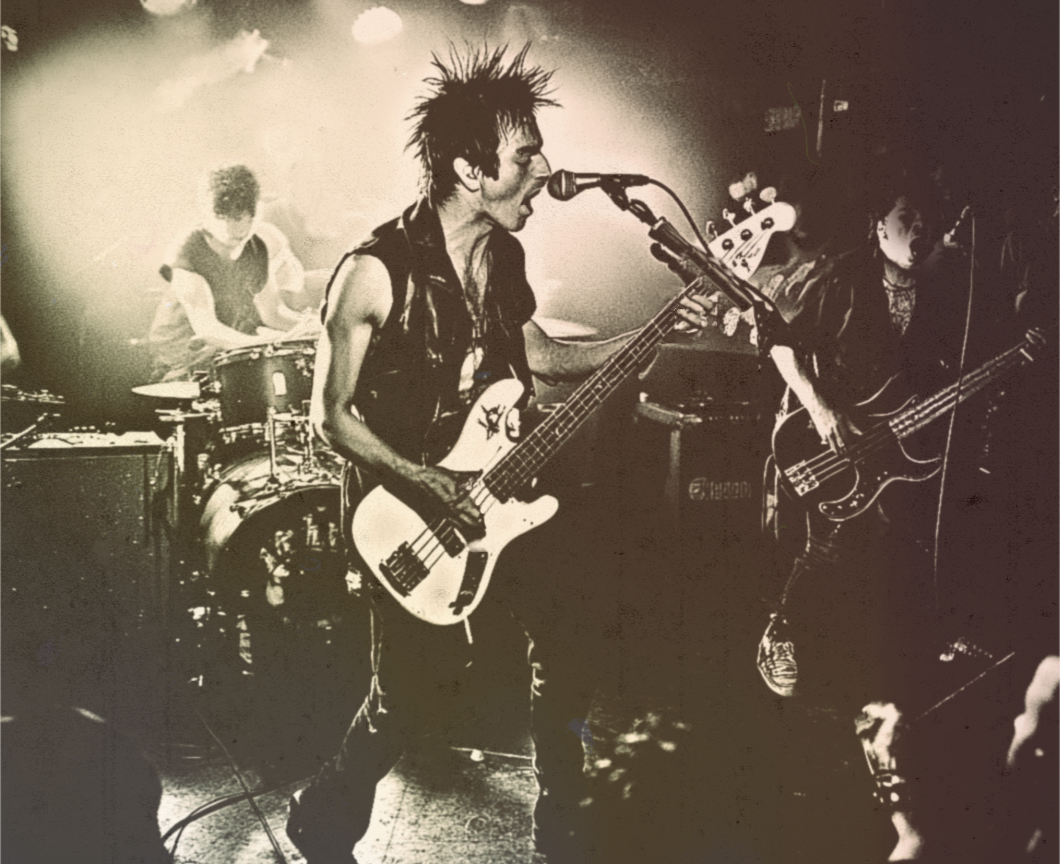

“I Saw Her Standing There” is no less radical. Its bass line, stolen with cheerful abandon from Chuck Berry’s “I’m Talking About You,” is itself a translation of Jerry Lee Lewis’s left hand — the rock and roll canon funneled through the neck of a left-handed Höfner bass. The guitars – both are essential - are sharp, percussive. The vocal is shouted and swung. It is proto-punk in energy and attitude: raw, fast, unapologetic. And all of this, recall, on a debut album.

Bob Dylan, whose praise is never lightly given, once said of the Beatles’ early work: “They were doing things nobody else was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid.”

That word — valid — is telling. The Beatles were not experimenting for novelty’s sake. They were expanding the permissible range of pop music while still working within its bounds. This was invention under constraint, and it takes a higher artistry to surprise within the limits than to disregard them.

What the Beatles did in these early songs was reassemble the fragments of American popular music — Everly Brothers harmonies, Berry rhythms, girl-group emotion, R&B vocal style — and bind them with a new kind of wit. Their gift was synthesis, but not imitation. The Beatles were not “influenced by” these forms; they subsumed them. They took Chuck Berry’s swagger and made it choral. They took the Everly Brothers’ close harmony and placed it atop hard-driving backbeats. They dropped the piano and sang with British accents, refusing the mimicry of their predecessors. They even added handclaps.

They created, in effect, a new genre — not just rock and roll, but something that could be called band-pop: a self-contained group that wrote, played, and performed as one, blending sophistication with adolescent joy. This model would become the default structure of popular music, but in 1963, it was unthinkably fresh.

It is only because of what followed — Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, Abbey Road — that these early miracles are taken for granted. But one cannot reach “A Day in the Life” without first discovering that a pop song can begin with a chorus, or end on a jazz chord, or explode with a “Yeah, yeah, yeah” that feels like youth itself shouting its arrival.

We live, today, in the long shadow of this early work. The melodic minimalism of punk and the Ramones, the punch of power pop, the anthemic, supersonic folk of U2, the postmodern pastiche of indie rock — all descend, in one way or another, from the form the Beatles forged while they were still being mistaken for a fad. Even The Clash’s late fusion of punk and reggae owes something to the Beatles’ early instinct for uncompromising synthesis — a restless belief that music could pull in every influence, every cultural signal, and still ring true.

These early songs are not preludes. They are the big bang.

And so we ought to listen again, and know the place again, for the first time. Not through the lens of later grandeur, but with simple gratitude and ears tuned to the small, spare room at EMI’s Studio Two; to the sound of young men – from Liverpool! - in matching suits, playing harder than they needed to, and laughing at the edge of musical history.

Not yet mythic. Not yet mystical. But utterly new.