Minimalism and the Condition of Complete Simplicity

/In eight words, Eliot offers a phrase that ought to be engraved above the entrance to every gallery of minimalism, every kitchen serving elemental dishes, every manuscript composed of restraint rather than flourish. For what he names is not austerity for its own sake, nor a fetish for sparseness, but a discipline of essence—the rare achievement of clarity without loss, of purity that still carries weight.

This essay is an about-face (or perhaps a complement), and rightly so. For while we have stood with skepticism before the musical altar of Pierre Boulez, whose Bruckner left the listener cold, now we turn toward something subtler, something harder to dismiss. For there are times when what is absent is not a sign of emptiness but of focus. Not every table demands a stew of game meats and root vegetables—a meal fit for a victorious war party of Vikings. Sometimes, what is called for is a consommé—clear, exacting, reduced to its essence. The key is not to confuse the two. Serve one when the other is expected, and disappointment will follow. But when the dish and the occasion align, even minimalism becomes a feast.

The modern eye has learned to spot this ethic in the visual arts, where Gerhard Richter’s “Grey Paintings”—particularly his Six Grey Mirrors at Dia Beacon—line the walls like quiet sentinels. Each surface, nearly uniform at first glance, reveals gradients, textures, and spectral reflections that reward prolonged attention, especially as light changes throughout the day. Gray, Richter once said, “makes no statement”—and yet in that non-statement, we discover the conditions of meaning itself.

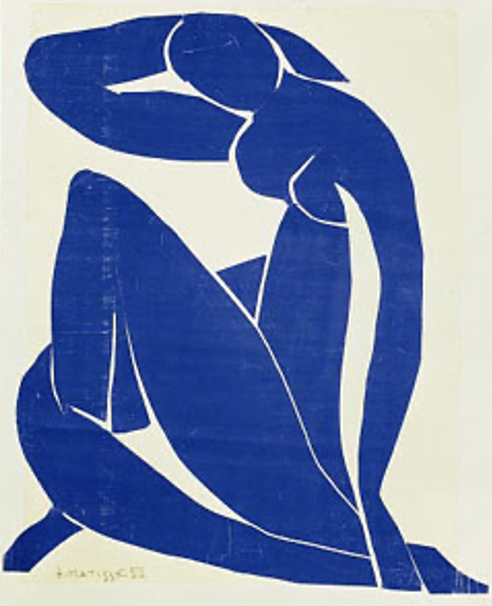

Henri Matisse

Blue Nudes

Or consider Henri Matisse, whose Blue Nudes reduce the human form to bold, curved shapes that carry with them not just visual elegance but emotional immediacy. There is no fuss, no rendering of detail, but the gesture is complete. Though neat, these images are powerful. Matisse once described his desire to create art “devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter... like a good armchair.” What he achieved, at his best, was not comfort but concentration—the beauty of presence without intrusion.

The culinary arts demonstrate this principle well. A perfectly ripe avocado, halved and sliced, served on a non-intrusive white plate, perhaps with just a dusting of sea salt, can be as satisfying—perhaps more so—than a twelve-course extravaganza. The presentation offers no garnish, because no garnish is needed. The color, the oily softness, the faint vegetal perfume—all speak in silence, and what is left out heightens what remains.

This is the minimalist ideal: not silence, but distilled speech. Not an absence of expression, but the refinement of expression into essence.

And so with that, we return to Boulez, this time with a different score in hand. His Anthèmes I, composed for solo violin, is a world apart from his Bruckner. Here, stripped of orchestral density and canonical weight, Boulez operates in a field where minimalism is not sabotage but strategy.

The piece begins with fractured tones, harmonics, isolated gestures that feel almost surgical. The violinist becomes less a performer and more a cartographer of sonic terrain. There are silences—but they are tense, poised, not blank. The listener is asked not to float along but to listen actively, to inhabit each creak of the bow, each whisper of a note. It is, in a sense, music as x-ray—a view into the bone structure of sound.

Does it move the heart as Mahler does? Perhaps not. But that is not its aim. Its success lies in its intensification through limitation, in doing much with little, in letting a single line bear the burden of form.

What minimalism demands—what Eliot understood—is not less effort, but more. Simplicity, if it is to carry meaning, must be intentional, exacting, and often ruthless in what it excludes. It must not simplify complexity into banality, but refine it until only the necessary remains. To do so costs not less than everything: it costs ornament, comfort, and sometimes popularity. But when it succeeds, it allows a clarity of encounter, a distillation of spirit.

It is something “like the stillness between two waves of the sea” as Eliot might say (and did, in fact, say).[1]

Minimalism is not the only path. It is not superior to density, to tradition, to musical or artistic abundance. But it is a path—and at its best, it is a clearing in the forest, a single voice in a cathedral, a plate with one perfect thing upon it.

In the end, it is not a matter of choosing between stew and consomme, between Mahler and Boulez, between abundance and restraint. The greater wisdom lies in knowing when each is called for, and why. For there are days when we need music that remembers the world, and there are days when we need music that forgets it—if only for a moment—to help us see it again, with new eyes so that we can “arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”[2]

This is Part 4 of 7 Essays

[1] T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding.

[2] T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding.