Boulez and the Disincarnation of Music

/It began with a sound—a non-sound, really. A listening session interrupted by suspicion: Did my headphones just break? Bruckner’s 8th Symphony, conducted by Pierre Boulez, was issuing forth not with the cathedral majesty I expected, but with a profound sense of absence. The massiveness of Bruckner had been hollowed out. The dynamic range was nominally intact, the phrasing precise, but something essential was missing. Not obscured—gone. It was, unmistakably, a consommé in place of a stew.

Later, while reading Roland Barthes, the French critic and semiotician, I had the same sensation—only this time, it came not as an absence but as a revelation. Barthes was describing how meaning is not fixed in words, but floats among differences; how a "text" is not a vehicle for essence but a play of signs. As I read, I realized: This is the sound I heard in Boulez. It wasn’t just an intellectual analogy. It was a metaphysical recognition. Barthes and Boulez, fellow Frenchmen of the mid-20th century, were not only inhabiting the same cultural world—they were creating the same world. The world of signs without signification, of form without metaphysical ground. The world, in short, of structuralism.

To understand Boulez’s music—and his interpretation of others’ music—it seems useful to me to begin with the intellectual revolution that surrounded him. In the early 20th century, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure proposed that language is a system of signs, each composed of a signifier (the word or sound) and a signified (the concept or meaning). Crucially, he argued that the relationship between the two is arbitrary. “Tree” doesn’t mean tree because of any inherent or historical quality—it means tree because of its place in the system, because it is not “free” or “three.”

This idea was taken up and extended by the French structuralists—Lévi-Strauss in anthropology, Barthes in literature, and eventually Foucault and Derrida, who turned it inside out. Their shared premise: meaning is not given, not essential, not revealed. It is constructed, differential, unstable. There is no center—only system. No presence—only structure. Even the author disappears; what remains is the “text” as a play of signifiers.

If this sounds cold, it is. It is a vision of human culture in which warmth, memory, and metaphysical weight are stripped away in the name of intellectual clarity. All skeleton, no heart and certainly no soul. And this is precisely the sound one hears when listening to Boulez.

Boulez’s music—and even more so, his conducting—reflects this worldview with eerie precision. His interpretations are crystalline, surgical, thin. Every note is accounted for, every line etched in glass. There is no indulgence, no rubato, no ritual pacing, no metaphysical sweep. The score is treated not as a sacred text but as a matrix. The result is perfectly intelligible but oddly uninhabited.

Take his performance of Bruckner’s 8th. What ought to be a slow-burning ascent into the realm of the sacred becomes something like a sonic schematic. The long phrases are painstakingly measured out in coffee spoons, not breathed. The climaxes are clean, not cataclysmic. The silences do not shimmer—they rest, empty. It is not that Boulez lacks control—he is nothing but control. What he lacks, or refuses, is presence.

It is this absence that startled me. And once I heard it, I could not unhear it.[1] Boulez wasn’t just playing Bruckner differently. He was performing a philosophical operation—the same one Barthes and Saussure performed on language, Lévi-Strauss on myth, Foucault on history. Boulez took Bruckner’s symphony and disincarnated it.

This is the great wager of the structuralist aesthetic: that structure is enough. That meaning, beauty, and expression are not grounded in metaphysical or historical realities, but emerge from the play of forms. For Boulez, this meant rejecting the romantic and the expressive, scorning sentimentality, and composing (or conducting) in such a way that the system speaks for itself.

In his own music, this led to intense serialism, mathematical constructions, and sonic experiments that often sound more like proofs than poems. As a conductor, it meant reading the score as a collection of signifiers on a page—not as testimony, confession, prophecy, or ritual. Music, for Boulez, is no longer the voice of Being (as it was for Mahler or Bruckner). It is a constructed language with internal coherence, but no transcendence. It is computer code, not Dostoyevsky.

Contrast this with Mahler—the tortured metaphysician of the orchestra.[2] Mahler’s symphonies are saturated with memory, with the ache of the lost sacred, with the terror of mortality and the ecstasy of revelation. They are metaphysical documents, confessions, liturgies. To perform them is not to map a structure but to inhabit a world.[3]

Consider: Leonard Bernstein, LSO - Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor "Resurrection", V. Finale (Excerpt)[4]

And contrast Boulez with Karajan (try this: Bruckner - Symphony No 8 in C minor - Karajan)—a conductor who, at his best, saturates the musical experience with atmosphere, depth, and density. Karajan doesn’t just connect the notes. He steeps them, layers them, cooks them into a stew of almost overwhelming emotional immediacy.

Boulez? He strains the liquid. What remains is clear, balanced, digestible—and thin. There is nothing wrong with consommé. But when one expects stew—needs stew—the result is disorienting, even disappointing.

The problem is not that Boulez is incompetent—he is formidably competent. The problem is that his aesthetic reveals a broader civilizational crisis: the collapse of confidence in presence, in spirit, in metaphysics. Boulez’s music is not devoid of content—it is content stripped of consequence. It sounds like it was written by a man who believes in language but not meaning, in notes but not music.

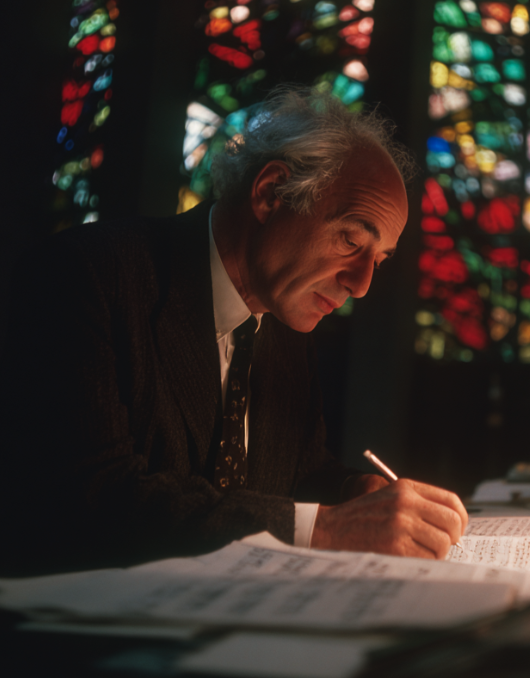

This is not an aesthetic failure so much as a philosophical one.[5] Boulez gives us the idea of the cathedral, rendered in blueprint. He gives us glass walls where once there were stained glass windows. He gives us performance without prayer.

Boulez was right about one thing: sentimentality is a trap. Melodrama is not drama; spectacle is not saga. But he mistook sentiment for spirit, and in purging the former, he lost the latter. In the age of structuralism, this was inevitable. His music is what happens when semiotics goes sonic.

But that is not the whole story. There is another essay to be written—a reconsideration. For while structure alone cannot save us, there are moments when clarity becomes revelation, when restraint reveals essence, when a single sliced avocado on a white plate is more honest than a full buffet. That is for another time.

For now, we must reckon with Boulez as a symptom—and perhaps a warning. He reminds us that it is possible to have perfect form and no incarnation, and to forget, in our brilliance, what the music was meant to be in the first place.

This is 3 of 7 essays.

[1] Or more accurately, I could not hear it any longer. I turned it off.

[2] It is reported that at the height of his renown, Mahler visited a composition class at a conservatory. A student asked something like, “how does one prepare to compose?” Mahler answered something to the effect of, “stop studying composition and just read Dostoyevsky”. This is both brilliant and terrible advice and no doubt contained an autobiographical clue about Mahler himself.

[3] You might say that listening to Mahler is like reading Lord of the Rings, but listening to Boulez is like looking at Tolkien’s maps and throwing away the novels.

[4] It is admittedly unfair to reference this famous performance in this context. But the point can also be overwhelmingly made, and Bernstein leaves us with no ambiguity here. This is not Boulez conducting.

[5] A full treatment of the ideas at work here would need to go all the way back to the French Revolution, and, in fact, everything that preceded it.