The Sublime, the Taboo, the Mythic, and the Dionysian: Wrestling’s Archetypes and the Transcendent Babyface

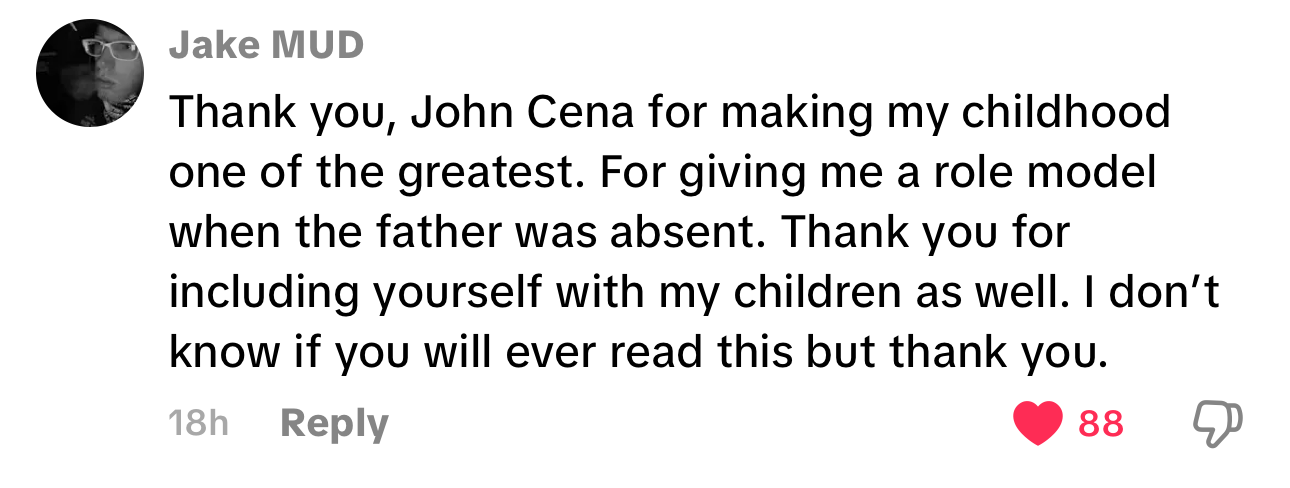

/In the previous essay, we noted that John Cena represents the real-life, human superhero—the performer who transformed a dramatic role into a source of personal rescue. To see the magnitude of that achievement, we must first understand the landscape from which he emerged. For professional wrestling, like opera, sustains a remarkable ecology of archetypes: forms that repeat across decades and territories, each with its own internal logic and mode of fulfillment. To understand John Cena’s transcendence, we must set him among those rare figures whose very being aligned with a dramatic form larger than themselves.

André the Giant perfected the sublime. His presence was not merely large but overwhelming—an encounter with physical impossibility. Audiences did not cheer André so much as witness him. He existed at the boundary between myth and biology, a living contradiction whose every movement disclosed the ancient terror and wonder of the giant. He was wrestling’s cathedral: towering, impossible, unforgettable. Truly, he will never be forgotten.

The Sheik perfected the taboo. Fire, blood, foreignness, fear—he embodied the shudder that ancient ritual evokes, the thrill and dread of transgression. The Sheik was not a villain in the moral sense; he was a villain in the anthropological sense, a figure from the underside of myth whose presence revealed the fragility of order. His wrestling was not sport but sacrament in the negative mode: chaos made flesh.

The Undertaker perfected the mythic. His matches were not contests so much as rites. His slow walk, his gesture of resurrection, his tolling bell—these were not theatrical gimmicks but dramatic invocations. If André was awe and Sheik was taboo, the Undertaker was cosmic order: death’s majesty rendered with operatic dignity. No one else has ever approached his ritual coherence.

And then there is Ric Flair, wrestling’s Dionysian genius. Flair perfected excess—not only material excess (robes, limousines, jewelry) but existential excess: the ecstatic edge where pleasure becomes madness and triumph curls toward tragedy. He was the celebrant-priest of wrestling’s intoxicating side, pouring his own life into the art until the boundaries dissolved. He lived the drama and burned through himself in the process. Nietzsche did not know Ric Flair when he described the Dionysian in The Birth of Tragedy—and yet, somehow, he did.

These four, André, Sheik, Taker, and Flair, show what it means to fulfill a dramatic archetype completely. Each reached a kind of completion—an alignment of body, persona, gesture, and myth that allowed the audience to encounter something elemental.

But none of them—and here is the key—achieved what John Cena achieved.

For André, Sheik, Taker, and Flair reveal truths about humanity through distance: the awe that dwarfs us, the chaos that threatens us, the myth that encompasses us, the ecstasy that shatters us. They embody forms that tower above or crash down upon the human scale.

But Cena reveals truth through proximity. Through recognition. Through the unsettling and consoling possibility that his struggle could be our own—that we, too, might rise up, endure, and do a little better. If André embodies the sublime and Flair the Dionysian, Cena embodies something rarer and more demanding: the human that can be heroic.

He began, of course, within wrestling’s most familiar role—the babyface, the good guy. The babyface archetype is old and honorable, but also limited. It has been inhabited by many, often briefly, as wrestlers turn from heel to face and back again. Historically, babyfaceness has been more emblem than enactment: a broad moral alignment, a gesture toward virtue rather than its full embodiment. Ricky Steamboat expressed it beautifully, Bruno Sammartino fiercely, Dusty Rhodes poetically, and Hogan mythically. These were complete expressions of the classical form.

But then came John Cena.

His heroism is not a style but a mode of being. The audience does not admire him from afar; they are drawn toward identification. They carry his slogans—“Never Give Up,” “Rise Above Hate”—not as catchphrases but as equipment for their own lives. Cena’s babyface is not performed; it is lived. And because it is lived, the audience can live it with him.

This is the ontological transformation Cena introduced into wrestling’s dramatic ecology. With him, the babyface ceased to be a symbol or a temporary alignment with virtue.

It became something new—something previously unimaginable.

It became a participatory practice.

The audience, in recognizing him, became co-bearers of his role. Cena ceased to be merely a character or an ideal; he became a shared existential resource. And for twenty-five years, the audience sustained him as he sustained them. This is beyond archetype. It is beyond wrestling’s classical taxonomy. It is a new mode of dramatic truth in which performer and audience create meaning together—a Gadamerian fusion of horizons within the squared circle.

For some wrestlers embody myth. But once in a rare while, a wrestler embodies hope.

And that is a role only John Cena could play.