Gulf Coast Refinery Economics: Crack Spread, Crude Sourcing, and Processing Capacity

/The complexities oil refining necessitate a keen understanding of its economics for effective profitability assessment. This is particularly the case in the Gulf Coast region of the United States, a hub for a significant portion of the country’s refining capacity. Two critical aspects to consider within the context of refinery economics are the crack spread and crude sourcing. Further, the refinery’s processing capability, particularly for heavy crude, is also a key factor.

The crack spread is a representation of the price differential between the feedstock for a refinery (crude oil) and its output (finished products), most notably gasoline and distillates such as heating oil and diesel fuel. Derived from the process of ‘cracking’; crude oil, where long-chain hydrocarbons are broken down into shorter ones, the crack spread offers economic insight into how refineries transform crude oil into many useful products.

The crack spread is simply the difference between the price of the refined products and the price of raw crude oil. It’s basically a gross margin calculation. It informs refiners about the potential profitability of converting crude oil into value-added products.

Crack spreads can be wide, signaling potential high profits if the price of refined products significantly surpasses the price of crude oil. And the crack spread can be narrow, indicating reduced profitability. Variations of the crack spread, such as the 3:2:1 and 5:3:2 spreads, reflect the gasoline and heating oil output from a given quantity of crude. The former assumes that three barrels of crude oil produce two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of heating oil, while the latter presupposes that five barrels of crude yield three barrels of gasoline and two barrels of heating oil. These ratios represent typical output from a U.S. Gulf Coast refinery, though these ratios can vary based on the type of crude oil processed and the specific technological capabilities of a refinery.

In terms of crude sourcing, Gulf Coast refineries have diverse domestic and international options. Domestically, these refineries can access oil produced in key U.S. regions, such as the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford Shale, and the Bakken Formation, from major U.S. oil companies or independent producers.

Internationally, refineries can import crude oil from various countries, with key sources traditionally including Canada, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and Iraq. The choice of supplier hinges on several factors, including the type of crude oil the refinery is equipped to process, the price, and transportation costs.

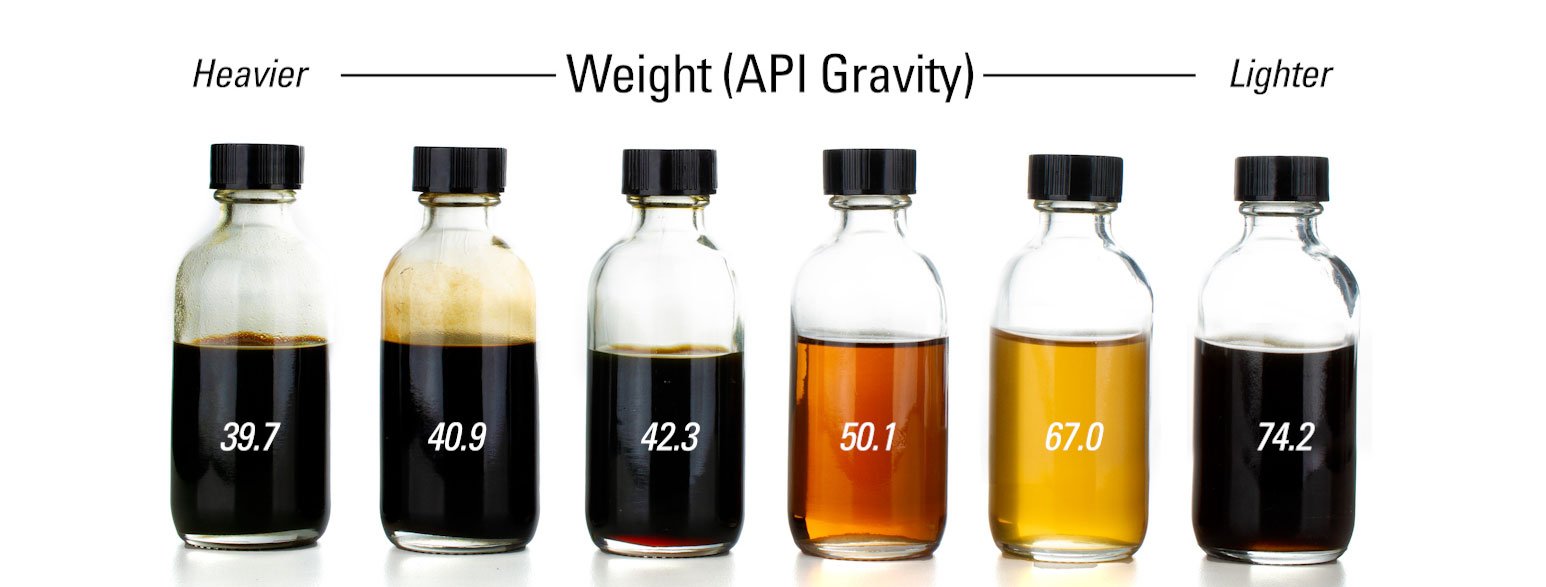

Many Gulf Coast refineries are particularly configured to process heavy crude oil. Heavy crude typically contains more complex, long-chain hydrocarbons, making it denser and more viscous than light crude. It often comes at a discount due to its lower quality and the increased processing required to refine it into end products. However, geopolitical issues can influence the availability of heavy crude. Sanctions on Venezuela (and the country’s extreme political turmoil) and declining production in Mexico have reduced their exports to the U.S. in recent years. In response, some Gulf Coast refineries have adapted to using lighter crudes, particularly with the surge in U.S. shale oil production. Nevertheless, still today, the inherent capacity for heavy crude oil processing remains a defining feature of the Gulf Coast.

In the dynamic world of Gulf Coast refinery operations, understanding the interplay between the crack spread, crude sourcing, and processing capability is crucial.

These factors not only guide refiners in managing their operations but also help stakeholders understand the industry’s health and trajectory. In the realm of refinery economics, the nuanced details often determine the profits.